Happy New Years everyone! Sorry about how long it took to post the update, but I was covering too many sections at once.

Darren Naish's post on Middle Jurassic British theropod femur OUMNH J29757 and "Scrotum humanum" led me to do something that's been on my list for a while- compare the one original figure of "Scrotum" to other theropods to see if is really Megalosaurus as has long been assumed. Turns out it's closer to another closely related taxon...

"Scrotum" Brookes, 1763

"S. humanum" Brookes, 1763

Aalenian-Bajocian?, Middle Jurassic

unknown quarry, Inferior Oolite?, Cornwell, England

Material- (lost) distal femur (~235 mm trans)

Diagnosis- (proposed) ectocondylar tuber limited to medial half of ectocondyle; ectocondyle subequal in size and shape to endocondyle.

Comments-

Originally described and illustrated by Plot (1677) as the distal femur

of a giant human, this is famous as being the first Mesozoic dinosaur

bone to be published. Brookes (1793) later summarized Plot's

description and opinions but labeled the specimen Sctrotum Humanum

in his plate. Rieppel (2022) notes that "At the top of page 317,

Brookes (1763) noted that 'other stones have been found exactly

representing the private parts of a man; and others in the shape of

kidneys . . . ', and continued further down on the same page" described

the femur. As "the plates and the individual figures they contain are

not numbered separately, but are identified by the pagination number of

the page on which the respective specimens are mentioned or described.

The conclusion seems to be that the illustrator took the femur fragment

to be an example of those stones referred to on page 317 as 'exactly

representing the private parts of a man', and erroneously labelled it

accordingly." Phillips (1871) believed it was from the Inferior Oolite

(Aalenian-Bajocian) and stated "It may have been the femur of a large

megalosaurus or a small ceteosaurus" without evidence. As described by

Delair and Sargeant (1975), Halstead (1970) "pointed out that because

of its date of publication (post-Linnean, i.e. after 1758), this

binomen can be considered a perfectly valid publication of the first

generic and specific name ever applied to dinosaurian remains. It is

perhaps fortunate that the name was not thereafter employed by any

subsequent worker, and thus Scrotum humanum Brookes must be treated as

a nomen oblitum and discarded." They (and Halstead) considered it more

probable to be Megalosaurus than Cetiosaurus

without evidence and stated "The specimen unfortunately is lost."

Halstead and Sarjeant (1993; publication duplicated in 1995) noted that

while Scrotum should be treated as a nomen oblitum under ICZN Article

23b (First Edition), "no application was made then, or has been made

since, for the formal suppression of Brookes's binomen." The Third

Edition of the ICZN came out in 1985 and eliminated the nomen oblitum

clause, so the authors petitioned the ICZN in 1992 "(I) to use its

plenary powers to suppress the generic name Scrotum Brookes, 1763 and the specific name S. humanum Brookes, 1763; (2) to retain on the Official List of Generic Names in Zoology the name Megalosaurus Buckland in Parkinson, 1822, type species by subsequent designation M. bucklandi Meyer. 1832. (3) to retain on the Official List of Specific Names in Biology the name bucklandi as published in the binomen Megalosaurus bucklandi (specific name of the type species of Megalosaurus

Buckland in Parkinson, 1822, by designation in Meyer, 1832); (4) To

place on the Official List of Rejected and Invalid Generic Names in

Zoology the name Scrotum Brookes, 1763; (5) to place on the Official List of Rejected and Invalid Specific Names in Zoology the name humanum Brookes, 1763, as published in the binomen Scrotum humanum,

and as suppressed in (1) above." as listed in 1993. As recalled by the

authors, Tubbs (Executive Secretary to the ICZN) replied later that

year that "The text on p. 301 of Brookes (1763) makes it quite clear

that the two words "Scrotum humanum" on the plate were a description of

a specimen, and that Brookes did not establish a genus Scrotum or a species humanum (any more than he did a species Kidney stone on the same plate!). The words just happened to be Latin." Furthermore, since "[the name Scrotum humanum]

has never been used as a scientific name", it "is therefore unavailable

under Article 11d of the Code" (Third Edition- "Names to be treated as

valid when proposed. - Except as in (i) below, a name must be treated

as valid for a taxon when proposed unless it was first published as a

junior synonym and subsequently made available under the provisions of

Section e of this article."). Finally, because "Plot's long-lost

specimen was ... not certainly, a Megalosaurus

bone", Tubbs wrote that "the Commission is willing to take action only

when there is an appreciable and real, as opposed to hypothetical,

threat to stability or nomenclature. This is not the case for Megalosaurus." Note that Tubbs was incorrect that Brookes ever specified Scrotum Humanum

was a description instead of a name, with page 301 being an unrelated

section on plant fossils, so his use of Article 11d was unwarranted

although recently supported by Rieppel's logic. He was also wrong

that it had never been used as a scientific name, as Molnar et al.

(1990) listed Scrotum humanum as a carnosaur nomen dubium. Under the current

ICZN, "Scrotum humanum" would be a nomen nudum based on Article 11.5-

"To be available, a name must be used as valid for a taxon when

proposed." Tubbs was right that the referral to Megalosaurus was merely hypothetical though, as it has never been supported by published evidence and seems unwarranted.

The femur is dissimilar from Cetiosaurus

(both the lectotype OUMNH J13615 and the Rutland specimen LCM

G468.1968) in being 45-86% larger, having a distally extended medial

condyle, and a fibular groove placed at the lateral edge. Note the

estimated transverse diameter is based on Plot's statement the

narrowest shaft circumference was 15 inches (= 381 mm) and scaled from

the figure. Compared to this, Megalosaurus

femora are slightly smaller (shaft diameter 265-343 mm), and differ in

having a more distomedially extended and pointed medial condyle, more

laterally positioned ectocondylar tuber, and a straight lateral edge

until the distal extent of the tuber. These same differences are also

usually present in e.g. Cruxicheiros, piatnitzkysaurids, Eustreptospondylus, Erectopus, Allosaurus, and Juratyrant

among large Jurassic theropods whose distal femora are undistorted and

figured in posterior view. If "Scrotum" is from the Inferior Oolite it

is also earlier than Megalosaurus, and differs from the contemporaneous Magnosaurus

in the same ways when preserved (more laterally positioned ectocondylar

tuber; straight lateral edge until the distal extent of the tuber),

although it could derive from Duriavenator with which it cannot be compared. Sinraptor dongi

is slightly more similar to "Scrotum" in having a convex lateral edge

alongside the ectocondylar tuber, but it is "Brontoraptor" which is

most similar in having that character, an evenly rounded medial condyle

and a more medially placed ectocondylar tuber. Torvosaurus

(ML 632) shows the last character at least but cannot be evaluated for

the rest, so "Scrotum" might be best characterized as a torvosaur and

may relate to "Megalosaurus" "phillipsi" from the Kimmeridgian of England that also has characters similar to "Brontoraptor" and Torvosaurus.

"Brontoraptor" also has a similar circumference (376 mm) and internal

cavity size based on Siegwarth et al.'s Figure 8E. Whether the

remaining differences (ectocondylar tuber limited to medial half of

ectocondyle; ectocondyle subequal in size and shape to endocondyle) are

genuine or illustration error caused by Plot generalizing then

unfamiliar megalosauroid anatomy is uncertain. Note "Scrotum" can be

excluded from Ceratosauria based on the absence of a tall anteromedial

crest, and from Coeluridae, Proceratosauridae and Maniraptoromorpha

based on the deep extensor groove described by Plot and large size

(with occasional exceptions, e.g. Yutyrannus).

References- Plot, 1677. The Natural History of Oxford-shire, being an

essay towards the Natural History of England. Oxford. 358 pp.

Brookes, 1763. The Natural History of Waters, Earths, Stones, Fossils and Minerals,

with their Virtues, Properties and Medicinal Uses: To which is added, the methods

in which Linnaeus has treated these subjects. Vol. 5. J. Newberry. 364

pp.

Robinet, 1768. Vue philosophique de la gradation naturelle des formes

de l'être, ou les essais de la nature qui apprend a faire l'homme.

Harrevelt. 260 pp.

Phillips, 1871. Geology of Oxford and the Valley of the Thames. Oxford at the

Clarendon Press. 523 pp.

Halstead, 1970. Scrotum humanum Brookes 1763 - the first named dinosaur.

Journal of Insignificant Research. 5(7), 14-15.

Delair and Sargeant, 1975. The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs. Isis. 66, 5-25.

Buffetaut, 1979. A propos du reste de dinosaurien le plus anciennement

décrit: l'interprétation de J.-B. Robinet (1768). Histoire et Nature.

14, 79-84.

Molnar, Kurzanov and Dong, 1990. Carnosauria. In Weishampel, Dodson and Osmolska

(eds.). The Dinosauria. University of California Press. 169-209.

Halstead and Sarjeant, 1993. Scrotum humanum Brookes - the earliest name

for a dinosaur? Modern Geology. 18, 221-224.

Halstead and Sarjeant, 1995. Scrotum humanum Brookes - the

earliest name for a dinosaur? In Sarjeant (ed.), 1995. Vertebrate

Fossils and the Evolution of Scientific Concepts; A tribute to L.

Beverly Halstead. Gordon and Breach. 219-222.

Delair and Sargeant, 2002. The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs: The

records re-examined. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 113,

185-197.

Rieppel, 2022 (online 2021). The first ever described dinosaur bone

fragment in Robinet's philosophy of nature (1768). Historical Biology.

34(5), 940-946.

Also updated is Chienkosaurus, which thanks to the recent description of Sinraptor dongi teeth by Hendrickx et al. (2020), I feel can be placed in Metriacanthosauridae. This and Szechuanosaurus were coincidentally recently reviewed by Curtice at his blog I've started following, Dr. BC's Hindsight at Fossil Crates, which I highly recommend.

Chienkosaurus Young,

1942

C. ceratosauroides Young, 1942

Tithonian?, Late Jurassic

IVPP locality 47, upper Guangyuan Group, Sichuan, China

Lectotype- (IVPP V237A) (~8 m) posterior premaxillary tooth (44x16x12 mm)

Referred- ?(IVPP V193) ulna (164 mm) (Young, 1942)

Bathonian-Callovian?, Middle Jurassic

IVPP locality 49, middle Guangyuan Group, Sichuan, China

?(IVPP V190) (~5 m) ~ninth caudal centrum (66 mm) (Young, 1942)

Other diagnoses- Young (1942) originally diagnosed Chienkosaurus

with- "Teeth thick and sharply pointed with fine palisade

denticulations on both sides. The anterior which are finer than the

posterior ones push lingually

towards the base and form a ridge topping at a distance before the base of the tooth."

Comments-

The material was discovered in late Spring 1941, with the type

consisting of four isolated teeth IVPP V237A-D. Young's (1942)

diagnosis was "Mainly based upon" the largest tooth (V237A), with the

three smaller teeth considered immature and (possibly incorrectly)

lacking their bases. He stated "The general shape of the teeth

resembles that of Labrosaurus stechowi" which was prescient as both are based on mesial dentition, and considered Chienkosaurus a ceratosaurid based on the questionably referred postcrania. Ironically, "Labrosaurus" stechowi is now thought to be ceratosaurid, but as Young noted Chienkosaurus lacks its lingual fluting which has proven to be a ceratosaurid character. Subsequently, Chienkosaurus

was generally placed in Megalosauridae (e.g. Romer, 1956; Steel, 1970;

Dong et al., 1978) when it was used as a waste basket for almost all

large Jurassic theropods including Ceratosaurus and later Yangchuanosaurus. Note Huene (1959) when citing Chienkosaurus as named in 1958 from the Late Cretaceous of Shantung meant to list Chingkankousaurus. Dong et al.

(1983) reported that "Rozhdestvensky (1964) proposed that the four

teeth of Chienkosaurus could

possibly belong to the Crocodilia" (translated), but which work this

corresponds to was not listed in the bibliography and cannot be determined. Dong et al.

also stated "during the editing of "The Handbook of Chinese Fossil

Vertebrates," Zhiming Dong conducted a review of these four specimens

and formally confirmed that the best preserved tooth among the V237

collection was a premaxillary tooth of a carnosaurian dinosaur, but

that the remaining three teeth were assignable to the crocodile Hsisosuchus." The dentition of Hsisosuchus

has not been described or figured in enough detail to distinguish it

from theropods, but two of the teeth (IVPP V237B and V237D)

are similar in being short and barely recurved with a high crown base

ratio, characters shared with the tooth figured separately in

Hsisosuchus' type description. They are provisionally placed in Hsisosuchus sp. here. The third supposed Hsisosuchus

tooth (IVPP V237C) is different in having a distinctly D-shaped section

with strong carinae somewhat like Guimarota tyrannosauroid premaxillary

tooth IPFUB GUI D 89, so is provisionally placed in Tyrannosauroidea

here. Retaining only one of Chienkosaurus'

syntype teeth in the genus would make it the lectotype, and as ICZN

Article 74.5 states "In a lectotype designation made before 2000,

either the term "lectotype", or an exact translation or equivalent

expression (e.g. "the type"), must have been used or the author must

have unambiguously selected a particular syntype to act as the unique

name-bearing type of the taxon", and Dong et al. explicitly make Chienkosaurus a synonym of Szechuanosaurus, and of Chienkosaurus'

syntypes only consider IVPP V237A to be theropodan, this is here

considered a valid lectotype designation. Rozhdestveksy (1977) earlier

listed Szechuanosaurus campi and Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides as "synonyms?" in his Table 1 without comment, while Dong et al.'s synonymization was based on examining Yangchuanosaurus

teeth from CV 00214 to correctly determine "the differences among

carnosaur dentitions are due only to being in a different position in

the dentition" and noting Chienkosaurus' and Szechuanosaurus'

types are from the same locality. While this indeed makes it possible

they even derive from the same individual, none of the teeth have been

shown to be diagnostic within metriacanthosaurids, and synonymization

should be based on autapomorphies or unique combinations of characters

instead of provenance. This synonymization of part of the Chienkosaurus type with Szechuanosaurus

was followed by Molnar et al. (1990) where they consider the taxon an

allosaurid, which makes sense as Dong was a coauthor. Most recently,

Hendrickx et al. included Chienkosaurus

in their cluster analyses, although the taxon is never mentioned in the

text, matrices or table of examined taxa. Classical/Hierarchical

clustering resolves it with Genyodectes, Sinraptor dongi (the only metriacanthosaurid analyzed there) and Allosaurus, while neighbour joining clustering resolves it sister to a clade whose basal members are 'Indosuchus' AMNH jaws, Allosaurus and S. dongi.

Young placed locality 47 at "the top part of the Kuangyuan Series and

immediately below the Chentsianyen conglomerate", now known as the

Guangyuan Group and the Chengqiangyan Group, with the former

corresponding to the Xiashaximiao Formation through the Penglaizhen

Formation. As it was found "immediately below" the boundary (layer 8b in Young et al., 1943), Chienkosaurus

may be from the Penglaizhen Formation or slightly lower Shuining

Formation. The age is listed as Tithonian on fossilworks and in

Weishampel (1990), the latter cited as from "Dong (pers. comm.)".

The tooth is similar to many large theropod teeth in general

characters, but is from the premaxilla as evidenced by the twisted

mesial carina and reduced extent of mesial serrations. The crown

base ratio (.75) is between the third and fourth premaxillary teeth of

Sinraptor dongi's holotype

(pm3 .60; pm4 1.04), which also match in size (pm3 FABL 16.87 mm; pm4

BW 12.26 mm) and in lacking mesial serrations basally. The cited

mesial (15 per 5 mm) and distal (6.7-10 per 5 mm) serration densities

are matched by teeth of S. dongi,

and the strong mesial carina Young describes could easily be due to the

"longitudinal groove adjacent to the mesial carina, on the lingual

surface of the crown" "clearly present in lpm3 and lpm4" as described

by Hendrickx et al. (2020) for S. dongi. Thus Chienkosaurus is indistinguishable from Sinraptor dongi

as far as can be determined from the description, and given its poorly

constrained age could be contemporaneous or even synonymous. Hendrickx

et al.'s matrices show no differences between Yangchuanosaurus shangyouensis (including Y. magnus), Sinraptor dongi and S. hepingensis that can be evaluated for Chienkosaurus,

so pending Hendrickx's in prep. study on metriacanthosaurid dental

anatomy the genus is considered Metriacanthosauridae indet..

Referred material- Young (1942) figured and described an ulna from the type locality (IVPP V193), stating he "would prefer to refer this ulna to Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides above described." The element is very different from Limusaurus

in having marked transverse expansions proximally and distally as well

as a triangular versus reniform proximal end, so that if Sinocoelurus is closely related to that genus the ulna is unlikely to belong to it. Eoabelisaurus has a much longer olecranon. The ulnae of megalosaurids and Kaijiangosaurus is far more robust with more proximally extended olecranons, while those of most coelurosaurs (e.g. Zuolong, Guanlong, Coelurus, Tanycolagreus, Fukuivenator) are much more slender with developed olecranons as well. Fukuiraptor

has a dissimilar ulna with a strong olecranon, prominent anteroproximal

longitudinal ridge and unexpanded distal end. This leaves several

roughly comparable taxa whose ulnae have been figured in

anteroposterior view- Ceratosaurus, Poekilopleuron, Yangchuanosaurus, Allosaurus and Haplocheirus. Young compared it favorably to the former, writing "it fits rather well with the ulna of Ceratosaurus nasicornis

(length of ulna, 17.7 cm.) which is only slightly longer than the

present form", and indeed the main difference in profile is the more

gradual proximal expansion laterally. However, in proximal view IVPP

V193 differs from Ceratosaurus and most other proximally figured ulnae in having a centrally placed olecranon (also seen in Coelurus, but not Tanycolagreus). While only photographed in anterior view, the ulna of Yangchuanosaurus (CV 00214) would also seem to have a centrally placed olecranon, so IVPP V193 may be correctly referred to Chienkosaurus/Szechuanosaurus after all.

Young

(1942) describes IVPP V190 as "A complete centrum of an anterior caudal

vertebra (or posterior lumbar) with length 66 mm., breadth 41 mm.,

minimum breadth of the centrum 24 mm", noting it "fit in size with Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides" and calling it Theropoda indet. in the plate caption but also saying there it "probably belonging to Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides." With a length/height ratio of 144% it is comparable to the ninth caudal of Sinraptor hepingensis

and indistinguishable in lateral view. It differs in being 85% wider

than tall vs. 95%, but this is within the range of variation in hepingensis'

caudals. Notably, this is from a different locality than the type,

said by Young to be in "the middle part of the" ... "Kuangyuan Series", layer 5a in Young et al. (1943),

and thus possibly corresponding to the Shangshaximiao Formation. Thus

while lacking a plausible connection to Chienkosaurus, it is congruent with being metriacanthosaurid but may also be e.g. piatnitzkysaurid or megalosaurid.

References- Young, 1942. Fossil vertebrates from Kuangyuan, N. Szechuan,

China. Bulletin of the Geological Society of China. 22(3-4), 293-309.

Young, Bien and Mi, 1943. Some geologic problems of the Tsinling. Bulletin

of the Geological Society of China. 23(1-2), 15-34.

Romer, 1956. Osteology of the Reptiles. University of Chicago Press. 1-772.

Huene, 1959. Saurians in China and their relations. Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 3(3), 119-123.

Steel, 1970. Part 14. Saurischia. Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology. Gustav Fischer Verlag. 1-87.

Rozhdestvensky, 1977. The study of dinosaurs in Asia. Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India. 20, 102-119.

Dong, Zhang, Li and Zhou, 1978. [A new carnosaur discovered in

Yongchuan, Sichuan]. Chinese Science Bulletin. 23(5), 302-304.

Dong, Zhou and Zhang, 1983. Dinosaurs from the Jurassic of Sichuan. Palaeontologica

Sinica. Whole Number 162, New Series C, 23, 136 pp.

Molnar, Kurzanov and Dong, 1990. Carnosauria. In Weishampel, Dodson and Osmolska

(eds.). The Dinosauria. University of California Press. 169-209.

Weishampel, 1990. Dinosaurian distribution. In Weishampel, Dodson and Osmolska

(eds.). The Dinosauria. University of California Press. 63-139.

Hendrickx, Stiegler, Currie, Han, Xu, Choiniere and Wu, 2020. Dental anatomy of the apex predator Sinraptor dongi (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) from the Late Jurassic of China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 57(9), 1127-1147.

|

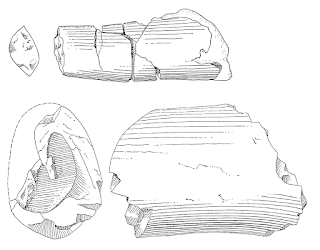

| Lectotype tooth of Chienkosaurus ceratosauroides in mesial and basal views (after Young, 1942). |

Also newly revealed to be metriacanthosaurid is "Yuanmouraptor"-

"Yuanmouraptor" Anonymous, 2014

Middle Jurassic

Yuanmou County, Yunnan, China

Material- (ZLJ 0115) partial skull, mandibles (one incomplete, one partial),

postcrania

Comments- This specimen is on display at the ZLJ as a new carnosaur,

but has yet to be described. There is a mounted skeleton, but how much is original

is unreported. Hendrickx et al. (2019) call this "an undescribed metriacanthosaurid (ZLJT 0115)", state it has mesial and

lateral teeth with "four to six, possibly more" flutes, and list it as

"Metriacanthosauridae indet." in their Appendix 1 indicating

information was from photos provided by Stiegler.

References- Anonymous, 2014. Special Exhibition: Legends of the Giant

Dinosaurs. Hong Kong Science Museum newsletter. 1-3-2014, 2-7.

Hendrickx, Mateus, Araújo and Choiniere, 2019. The distribution of

dental features in non-avian theropod dinosaurs: Taxonomic potential,

degree of homoplasy, and major evolutionary trends. Palaeontologia

Electronica. 22.3.74, 1-110.

As part of a review of Jurassic Chinese theropods, I went over the largest Jurassic theropod, previously referred to Szechuanosaurus campi.

unnamed averostran (Camp, 1935)

Middle Jurassic?

Jung-Hsein UCMP V1501, middle Chongqing Group, Sichuan, China

Material- (UCMP 32102) (~14.7 m) mesial dentary tooth (~69x~22x? mm), rib fragment, ischial fragment, femoral fragment (~1.33 m)

Comments-

The specimen was collected on August 30 1915 by Louderback. Note the

UCMP locality number is V1501 (as determined in their online

catalogue), not V151 as listed by Camp. Jung-Hsien is now called

Rongxian, a county in Zigong City. Camp stated "The beds in which they

occur have been called the Szechuan series", which was a term for the

stratigraphic section from the Early Jurassic Qianfuyan (= Tsienfuyan)

Formation and Ziliujing (= Tsuliuching, = Tzeliutsin) Formation to the

Cretaceous Chengqiangyan (= Chengtsiangyen) Group and Jiading (=

Chiating, = Tshiating) Group, depending on north versus south in the

Sichuan Basin. Rongxian is located in the south, so UCMP V1501 would be

part of the Ziliujing-Chongqing-Jiading sequence, and Young (1937; see

also Young et al., 1943) placed it above the Ziliujing Formation but

below the conglomerates of the Jiading Group, and thus within the

Middle-Late Jurassic Chongqing Group. Furthermore, Young (1937) stated

"The fossiliferous horizon discovered by Louderback lies probably

between our horizons 2 and 3, some 200 meters above horizon 2" which is

the type locality of Omeisaurus junghsiensis. As Omeisaurus

is generally recovered in the Xiashaximiao Formation and horizon 3 is

another 300 meters above where Young placed UCMP V1501 (so may be the

Penglaizhen or Suining Formation), UCMP 32102 may derive from the

Shangshaximiao Formation. Dong et al. (1983) listed it as deriving

from that formation, perhaps using the same logic although they did not

describe any explanation.

Camp (1935) initially referred the specimen to Megalosauridae because

histology "shows quite definitely that the relationship of the Chinese

form is with Allosaurus" instead of Tyrannosaurus. However, the plate shows this is because the sampled section of Tyrannosaurus femur (labeled AMNH 5886, but this is the Anatotitan paratype, and it is more probably Dynamosaurus holotype AMNH 5866 that is known to be histologically sampled) is composed of secondary osteons, while those of Allosaurus and UCMP 32102 are fibrolamellar bone. Yet Allosaurus

can develop secondary osteons where bone is redeveloped as well (e.g.

MHNG GEPI V2567a), so this isn't a real difference between these taxa.

While Camp wrote "a projection of the borders would indicate an

original total length of at least 90 mm" for the tooth, he also

repeated Osborn's 1906 statement that Tyrannosaurus

(CM 9380 and NHMUK R7994) teeth are up to 125 mm, which includes the

root. Combined with his statement the serrated distal carina "reaches

the base of the enamel" and serrations are not illustrated on the most

basal section, the actual crown length would have been about 69 mm.

Similarly, Camp wrote "At the base it is 17 mm. in longest diameter",

but scaling the figured tooth to the stated preserved length of 60 mm

results in a FABL of 22 mm instead. Young (1942) later wrote "The

general structure of [Szechuanosaurus campi

syntype] V236 with the way of serrations fits so well with the

Junghsien tooth, we feel that there is practically no doubt in

regarding them as identical" "and prefer to consider the Junghsien

tooth as belonging also to the new form" Szechuanosaurus. This despite previously stating UCMP 32102 "is bigger and straighter than all" Szechuanosaurus syntype teeth. Compared to Sinraptor dongi and Szechuanosaurus,

UCMP 32102 is larger (~69 vs. up to 63 vs. ~32 and ~47 mm), with a much

greater crown height/base ratio (~314% vs. up to 244% vs. ~224% and

~267%), making it less tapered. The crown section is similar to Allosaurus' fourth dentary tooth and the mid crown ratio of 53% is similar to dentary teeth in S. dongi and between S. campi IVPP V238B and 238C. As in mesial teeth of S. dongi,

the crown is slightly lingually curved and the mesial carina does not

reach the crown base. The same serration densities (mesial 15 per 5

mm, distal 6.7-10 per 5 mm) can be found in S. dongi as well, but are lower than S. campi

(distal ~12-19 per 5 mm). Dong et al. (1983) wrote "Camp's description

and the dentition size suggests it may be assignable to Yangchuanosaurus", but it is larger than even the magnus

type (up to 75 mm), and more elongate than the largest maxillary teeth

of the genotype (crown height/base ratio of 267%), but detailed dental

statistics of the genus have yet to be published. The femoral fragment

is notably large, Camp stating the shaft has "an enormous hollow cavity

about 125 mm. in the longest diameter of its ellipse. The greatest

diameter of this segment at its narrowest point is 20 cm." Based on

the absence of a fourth trochanter or medial narrowing, the section is

just distal to the former structure. Here large theropod femoral

shafts are wider than deep, so 200 mm would be the width and the

figured depth is then ~143 mm. Scaling from the largest

metriacanthosaurid, Yangchuanosaurus magnus,

results in a femoral length of ~1.33 meters, not far from Camp's

"estimated total length of about 140 cm." The ischium "consists of a

moderately hollow shaft spreading into a broader, solid plate", which

could describe most non-maniraptoran ischia, while the "tip of a large

rib" is not described. Notably, the ischium was found 37 meters from

the other material, so its association is less certain.

Given the above information, UCMP 32102 is different from the Szechuanosaurus syntypes and anteriorly straighter than Sinraptor

as well, and is perhaps the largest known Jurassic theropod. As no

characters are outside the range of ceratosaurids, it is considered

Averostra incertae sedis here.

References- Camp, 1935. Dinosaur remains from the province of Szechuan.

University of California Publications, Bulletin of the Department of Geological

Sciences. 23(14), 467-471.

Louderback, 1935. The stratigraphic relations of the Jung Hsien fossil

dinosaur in Szechuan red beds of China. University of California

Publications. Bulletin of the Department of Geological Sciences.

23(14), 459-466.

Young, 1937. New Triassic and Cretaceous reptiles in China (With some

remarks concerning the Cenozoic of China). Bulletin of the Geological

Society of China. 17(1), 109-120.

Young, 1942. Fossil vertebrates from Kuangyuan, N. Szechuan, China. Bulletin

of the Geological Society of China. 22(3-4), 293-309.

Young, Bien and Mi, 1943. Some geologic problems of the Tsinling. Bulletin

of the Geological Society of China. 23(1-2), 15-34.

Dong, Zhou and Zhang, 1983. Dinosaurs from the Jurassic of Sichuan. Palaeontologica

Sinica. Whole Number 162, New Series C, 23, 136 pp.

|

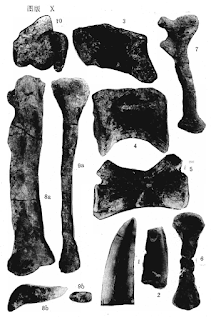

| UCMP 32102 tooth (top) and femoral shaft (bottom) (after Camp, 1935). |

Finally, I've been translating He (1984), so here's that publication's supposed Szechuanosaurus-

unnamed Tetanurae (He, 1984)

Bathonian-Callovian, Middle Jurassic

Hexi Commune, Shangshaximiao Formation, Sichuan, China

Material-

(CUT coll; = CCG coll) (multiple individuals) many teeth (~63 mm),

anterior cervical centrum (~68 mm; immature; Fig. 6-16, Pl. X Fig. 3),

mid cervical vertebra (~69 mm; Fig. 6-17), tenth cervical centrum

(immature; Fig. 6-19a), ~second dorsal centrum (~55 mm; immature?; Pl.

X Fig. 4), incomplete ~fourth dorsal vertebra (Fig. 6-19b), mid dorsal

centrum (immature; Fig. 6-19c), more than forty caudal vertebrae

including proximal caudal vertebra (Fig. 6-19d) and distal caudal

vertebra (~70 mm; Pl. X Fig. 5), incomplete coracoid (~98 mm

proximodistally), humerus (265 mm), ischium (~356 mm), femur, tibia

(~730 mm), fibula (~709 mm) and unguals

Comments-

He (1984) states that in 1964, 1979 and 1980 in Chengdu the institute

(= CUT) "conducted systematic collections in Hexi Commune (near Huomu

Station) in the suburbs of Qingyuan City, including many carnosaur

specimens, including many teeth, cervical vertebrae, dorsal vertebrae,

more than forty caudal vertebrae, complete ischium, femur, tibia and

fibula, as well as relatively complete humerus, coracoid and claws."

(translated) He referred these to Szechuanosaurus campi

because the syntypes were also found in the suburbs of Guangyuan and

believed to be from the Shangshaximiao Formation based on faunal

similarities and fossil abundance, "there is no significant difference

in shape and size" between S. campi

and the Hexi teeth, and "there is no evidence of the existence of two

or more carnosaurs" from that horizon. However, the teeth of S. campihave

not been shown to be diagnostic within e.g. Metriacanthosauridae,

multiple taxa with megalosaur-grade teeth are now known from the

Shangshaximiao (Leshansaurus, Yangchuanosaurus shangyouensis, Sinraptor hepingensis), and S. campi itself may be from the Penglaizhen Formation or slightly lower Shuining

Formation instead. Furthermore, He notes "that the tooth size in this batch of Szechuanosaurus campi

material we collected is quite varied, which means that in addition to

the differences in individual size, there may also be immature

specimens, because some vertebral centra and neural arches are unfused.

The largest individual is comparable to the type of Yanchuanosaurus shangyouensis

[sic], and the smallest individual is estimated to be only 4-5 meters

in length." Thus multiple individuals and perhaps multiple taxa

are involved, with only the tibia and fibula in Plate X Figures 8-10

being claimed to be from one individual. Note while Chure (2000)

mentioned a metatarsal as being in this material, He does not indicate

as such and Chure might have mistaken Plate X Figure 6 which is a

humerus. Indeed, Chure seems not to have translated the text so

understates the preserved vertebral number and misses the reference to

unguals. Yang et al. (2021) later describe the humeral histology, noting their Szechuanosaurus specimen is from Hexi and citing He's paper. This paper confirms the material "contains several incomplete individuals with large differences in size" (translated), that "The

specimen is currently preserved in the Museum of Chengdu University of

Technology" and that it was recovered from the Shangshaximiao Formation

at the same locality as Mamenchisaurus "guangyuanensis". "One

of the medium-sized individuals was recovered, mounted and exhibited",

which is photographed in their Figure 2, although it cannot be

determined what material is real and what is plaster.

This material was originally referred to Megalosauridae by He (1984)

based on tetanurine plesiomorphies (large teeth, short presacral

vertebrae, distally expanded ischium), while Chure (2000) placed it in

non-avetheropod Tetanurae based on the supposed lack of a posterodistal

coracoid process and subglenoid fossa, although Figure 6-18 of He

clearly shows both. Although Chure believes the information

available in the literature "make(s) it impossible to refer this

material to any family" and considered it indeterminate, the figures

and plates suggest otherwise. Among Late Jurassic theropods, the

slightly opisthocoelous cervicals are only known in piatnitzkysaurids

and coelurosaurs, with the long and low neural spines being unlike most

contemporary non-coelurosaur theropods, meaning the mid cervical

vertebra at least is not megalosauroid or carnosaurian.

Similarly, the large coracoid tubercle is unlike basal tetanurines and

more similar to ceratosaurs or coelurosaurs, although lacking the

hypertrophied size of the former. As suggested by Chure, the

ischium does resemble Megalosaurus in the ventral kink of the shaft and boot morphology, although it is much more robust, thus a referral to Leshansaurus is plausible. The tibia on the other hand is more similar to Sinraptor

in the anteroposteriorly short proximal end and anteroposterior

compression distally, so may be metriacanthosaurid. Based on this

brief comparison, the material deserves restudy and probably represents

multiple tetanurine taxa.

References- He, 1984. The Vertebrate Fossils of Sichuan. Sichuan Scientific

and Technical Publishing House, Chengdu, Sichuan. 168 pp.

Chure, 2000. A new species of Allosaurus from the Morrison Formation

of Dinosaur National Monument (Utah-Colorado) and a revision of the theropod

family Allosauridae. PhD thesis. Columbia University. 964 pp.

Yang, Liu and Zhang, 2021. The humeral diapophyseal histology and its biometric significance of Jurassic Szechuanosaurus campi (Theropoda, Megalosauridae) in Guangyuan City, Sichuan Province. Acta Geologica Sinica. 95(8), 2318-2332.

Additional references- Siegwarth, Lindbeck, Redman, Southwell, unpublished. Giant carnivorous dinosaurs

of the family Megalosauridae from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of eastern

Wyoming. Contributions from the Tate Museum Collections, Casper, Wyoming. 2,

40 pp.

Benson, 2010b. The osteology of Magnosaurus nethercombensis (Dinosauria,

Theropoda) from the Bajocian (Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom and a re-examination

of the oldest records of tetanurans. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8(1),

131-146.

Benson, 2010b (online 2009). A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda)

from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods.

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158(4), 882-935.

What would we define as a "torvosaur" within Megalosaurinae in terms of phylogenetic taxonomy? Min ▽ (Weihenvenator & Torvosaurus)?

ReplyDeleteGiven the uncertainty in megalosauroid phylogeny, I'd prefer a stem-based definition with several external specifiers - (Torvo < - Megalo, Afroven, Eustrep, Spino, Allo). But I'll also note that published support for such a clade is not well established, with Rauhut et al. (2016) never stating what characters support placing Wiehenvenator there, and "Brontoraptor" being assumed to be Torvosaurus without rationale.

DeleteIndeed. The concept of carnosaurian megalosauroids seems more and more compelling with time, so such a definition is undoubtedly more sound. I'd love to see a proper comparison between Edmarka, "Brontoraptor", and Torvosaurus one day, though perhaps that's a pipe dream.

DeleteI see they list "the presence of a laterodorsal ridge within the anteroventral part of the antorbital fossa; the premaxillary contact is slightly inclined posterodorsally so that its dorsal end is placed at about the level of the posterior margin of the first alveolus; remarkable similarity of the jugal ramus; similarity of the size of the antorbital fossa" at least as similarities between T. tanneri, T. gurneyi and Weihenvenator but that is all I could find in the paper, I'm sure there's more. But, forgive me, as I'm a beginner when it comes to anatomical diagnoses; I assume the problem is that they never explicitly state any diagnostic synapomorphic characters anywhere concerning this alleged sister group?

Why do you separate Edmarka & "Brontoraptor" from Torvosaurus when you agree that Bakker's taxa are otherwise usually invalid?

ReplyDeleteDo I agree with that? The latest study suggested Denversaurus was valid, yahnahpin is considered a valid species of apatosaurine, and no one has provided data on Edmarka versus Torvosaurus. Apparently Drinker is Nanosaurus, but besides that Chassternbergia and Nanotyrannus are new genera for existing species and Bakker was right that the latter wasn't Gorgosaurus. As stated on the Database, Carrano et al. (2012) merely state "Brontoraptor" and Edmarka "may represent species level variants of Torvosaurus, but we do not consider the observed differences as sufficient to justify a new taxon at this time", which is an empty argument.

DeleteDo you agree with Soto et al. (2020) that "Megalosaurus" ingens is another torvosaur?

ReplyDeleteHaven't looked at any of their papers yet, which is quite sad as they do acknowledge me. But it is on the list.

DeleteInterestingly Carano (2006) reports a 120 cm femur length for Yangchuanosaurus

ReplyDeleteThere is also another Giant Jurassic theropod, which is an unnamed Megalosaurid from Vaches Noires known from a single premaxilla (B1). The premaxilla is 17 cm tall and 16 cm long. The Dry Mesa specimen has a 14.8 cm tall and 14.5 cm long premaxilla, making B1 ~13% larger than the Dry Mesa specimen. Edmarka jugal is only 5% larger than that of the Dry Mesa specimen.

ReplyDeleteSo, this may be a hair brained question, and I know it's a little off the topic of this post but I didn't know where else to go to ask it, and I know you know your stuff: do you know if anyone has looked into the possibility of Nanuqsaurus hoglundi as an alioramin? With a putative therizinosaur from the same region, Asian taxa have precedent..

ReplyDeleteWhat's the reference to an Alaskan therizinosaur? But in regard to Nanuqsaurus being an alioramin, I would expect one of the analyses Fiorillo and Tykoski ran to place it there if there were any character support, and just offhand the robust dentary doesn't resemble even the largest Alioramus ('Qianzhousaurus').

Delete